I’m spending more time outside this summer than I have in years, mostly walking but sometimes reading poetry and sipping tea on the porch. Or, as now, enjoying time at a small French Bakery and Bistro before the afternoon heat arrives.

I arrived early to meet a friend and spent twenty minutes walking around the neighborhood then returned to La Chatelaine and waited. When my friend didn’t appear, I texted: “What a beautiful morning for coffee and a chat! I’m here.” He responded: “Oh no! Not this Wednesday. Next Wednesday. So sorry for the misunderstanding.” He was right. His text had clearly stated next week as a good time to meet.

Not to squander the opportunity to sit outside at the lovely café, I bought a coffee and pastry, borrowed a pen from the young woman at the counter (Couldn’t believe I didn’t have a pen along with the notebook in my cavernous purse!), and returned outside to the cool morning.

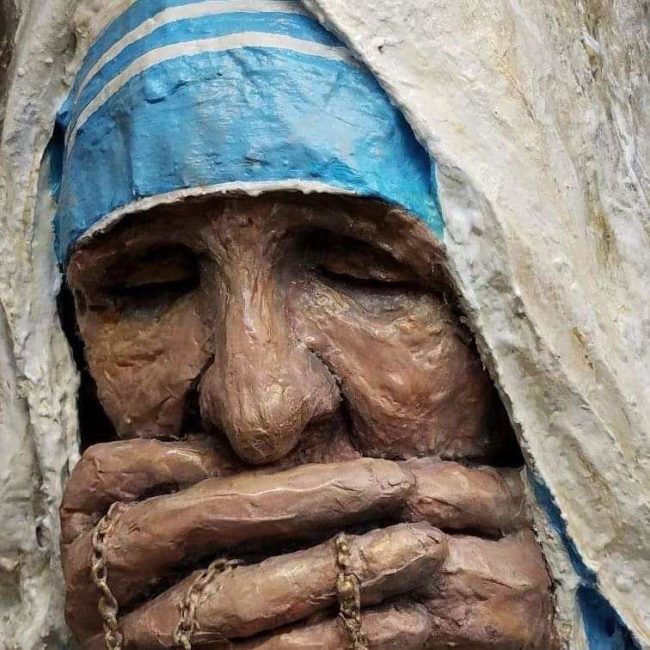

Traffic picked up, and several people went into the Bistro and emerged carrying coffees or breakfasts to go. An ambulance sped by; its sirens blaring. A quiet Hail Mary sprang to my lips, an enduring practice ingrained by the nuns in Catholic elementary school. A siren meant someone was in trouble, unexpectedly sick, or had been in an accident. They were in need, and when we heard one, we stopped our work and prayed for them.

Sixty years later I still do, though not always a Hail Mary. More often I utter something simple like “Help them. Love, be with them.” Or maybe I hold them silently in my heart as I am mindful of the Holy One, the healer and comforter, present to them in the moment.

I don’t hesitate to whisper into the Sacred ear a reminder to hold the suffering person a bit closer and to fill the hearts of those caring for them with compassion. I figure even the Holy One can use a reminder. “Don’t forget this one,” I say. It’s the mom in me. I know she’ll understand.

The ambulance passed, and I turned to my notebook. I love coming to this place. Perhaps because it’s not the inside of my modest apartment or because it reminds me of time spent in Parisian cafes. Or maybe because it is what it is: A charming space on a busy American street that offers amazing French pastries and an outside area to sit around tables under big canvas umbrellas, a shady canopy so like the green ones in Parisian parks.

I savored the last bit of flaky palmier that tasted like the creme horns I devoured as a child when mom gave us a few quarters to spend at the bakery as she shopped at the grocery next door.

Palmiers have no filling nor the cloying sweetness of the thick, sticky cream that filled my childhood treats, but the flavor is similar enough to bring back memories with each bite. I push the empty plate away, an offering for the sparrows that scavenge on the patio and tables to feast on crumbs patrons leave behind.

“How lucky to be able to do this,” I thought. “To sit. Feel cool air. Watch traffic. Sip coffee and write in my notebook.” It’s the life I imagine that I want and then am sometimes surprised to discover I already have. While not near the ocean, the perennial pull for me, it is in a place of relative peace. There are no bombs dropping. No war at my doorstep. I can enjoy the sounds of friends meeting for breakfast or indulge in conversation with a guy who walked from his office to work outside.

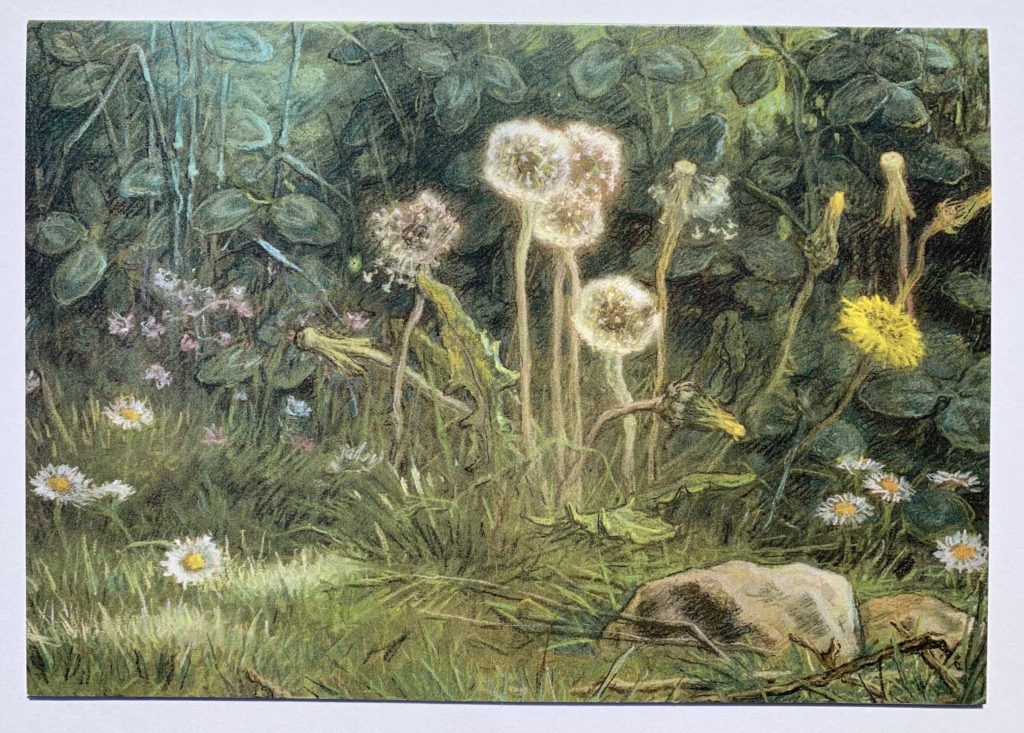

Following the sparrows, my eyes moved to their perches on gnarly branches that spread from two, low-growing trees bordering the patio. The twisted lines, the mottled bark of browns and greys begged to be sketched or painted. They reminded me of trees in some of van Gogh’s work or Monet’s. I took a few photos, thinking I might give it a try.

Overwhelmed by the moment, I moved into quiet prayer, filled with wonder and gratitude for Divine Life stirring within, swirling without. Freely given. The simple but transforming experience that pulls us all into the circle of mystics: experiencing communion with Holy Mystery right where we are. Eventually I opened my notebook, clicked my borrowed pen, and guided it over the pages. Words and more words. They helped me unpack the morning’s glory. They are my prayer of thanksgiving.

He and his wife were busy folding loads of laundry and sorting it into piles for each of their four children. They were preparing for a month-long trip to visit both sets of grandparents and, in addition to that, camping for a week. In the midst of their preparations, they offered hospitality to a visiting aunt, which would be me. And of course, all four children were around, talking to their visitor and taking care of their own preparations—which may have included cleaning rooms and gathering books to take. I leave it to your imagination. Not a lot of time there to sniff the laundry.

He and his wife were busy folding loads of laundry and sorting it into piles for each of their four children. They were preparing for a month-long trip to visit both sets of grandparents and, in addition to that, camping for a week. In the midst of their preparations, they offered hospitality to a visiting aunt, which would be me. And of course, all four children were around, talking to their visitor and taking care of their own preparations—which may have included cleaning rooms and gathering books to take. I leave it to your imagination. Not a lot of time there to sniff the laundry.