Sometimes life delivers a reminder of the Glory it holds, like this week while I meandered through a small park running along the west bank of the Scioto River. The park was empty except for a few walkers and two knots of birders gazing up into the trees. They carried a variety of cameras and binoculars, some with lenses long and heavy enough to require extra support. It was migration season. Non-resident birds and ducks were traveling through. I’m a casual bird watcher with a life-list begun decades ago where, if I remember, I check off a bird when I see it for the first time. My list is a record of what I’ve been graced to see, not a guide for what I have left to find.

“Hi. What are you looking at?” I asked good-naturedly, observing six feet of social distance.

“Nothing!” an irritated woman spat out. “Nothing! There is nothing to see here.”

I looked around at the surroundings, brimming with spring flowers and trees in various stages of leafing out. The river reflected the sun, and an occasional heron sailed by the white clouds.

“Really? Nothing? My sister and her husband saw a black -billed and a yellow-billed cuckoo here yesterday,” I said, trying to sound like I knew a little about the hobby. I was thinking “you just never know what will show up,” and thought I delivered the comment in a hopeful kind of way.

“Yesterday. Figures. The thing is, they were here yesterday. I wasn’t!”

No, she wasn’t. The problem, as I saw it, was that likely she wasn’t present in the morning’s moment either. Not really. Her experience was constricted by an agenda, and the park wasn’t delivering. I continued my walk, and despite the disgruntled woman’s claim that there was nothing worth seeing, I found plenty. Actually, her outburst, uncharacteristic of birders in general, heightened my openness to the surroundings.

First to catch my eye were dandelions, some sunny yellow and others holding delicate silver globes of parachuted seeds, waiting for a breeze to send them flying. They mingled with fuzzy, thick- stemmed plants sending up shoots topped with a clenched cluster of buds. I leaned in for a closer look. The spotted early earth-hugging leaves gave it way: waterleaf.

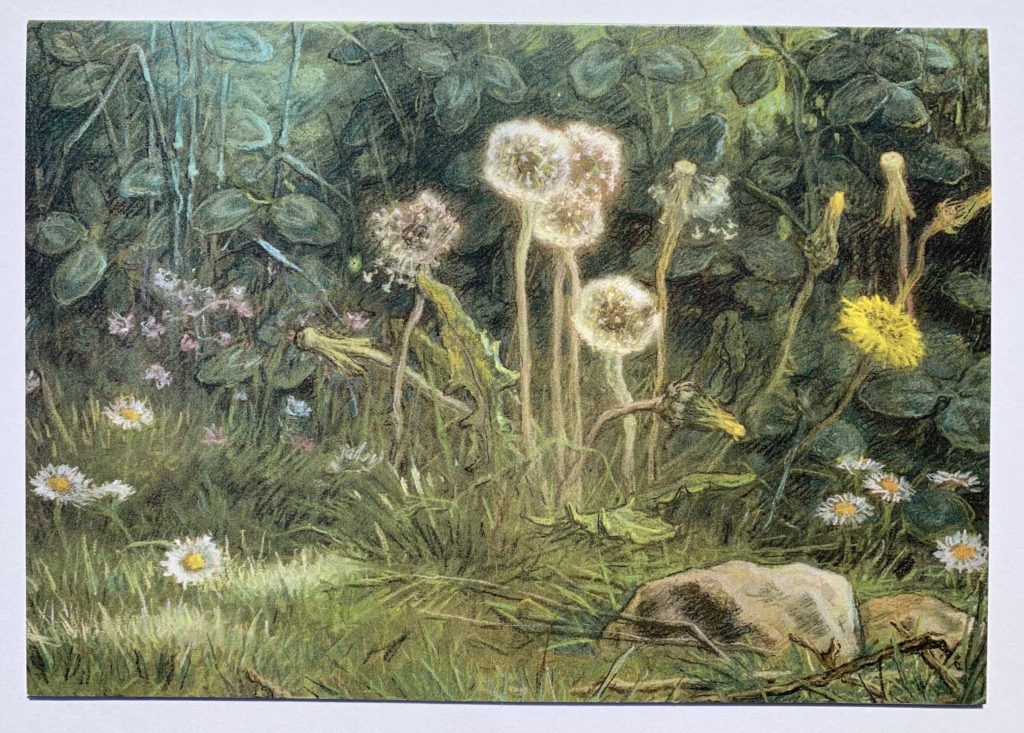

The scene reminded me of a pastel drawing at the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston: “Dandelions,” by Jean-François Millet. His detailed drawings highlighted the flowers’ beauty and caught my attention immediately upon my entering the exhibit. “A kindred spirit,” I’d thought. I’m not an accomplished artist, but when I draw, I work small and focus on common treasures.

Pastel on tan wove paper

Jean-François Millet

Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

There were lots of other things to see in the park. Oak, sycamore, maple, locust, and hickory trees. White honeysuckle blooms wet with nectar. The small stream, last week singing with water splashing over its rocky bed, diminished by hot, dry days.

I followed the lichen covered stone wall reminiscent of those crisscrossing fields in New England and the Robert Frost poem that made them famous. In a patch of wildflowers and grasses left to grow wild, bluebells were fading and ground-hugging violets stole the show.

The path stopped at the river. Mallards were gliding past, and farther out, a ruddy duck disappeared under the water again and again. I stood a while, soaking in the scene and then turned to walk back to my car.

The birdwatchers were still gathered in the same place, but this time cameras were clicking.

“What’d you find?” I asked.

“A Blackburnian warbler,” a gentleman replied and guided my eyes upward to a small silhouette perched on slender tree-top branches. Lifting my binoculars, I found the bird, stunning with black, white, and orange markings. Closer to my car, a Baltimore oriole flamed bright on a tree branch. An embarrassment of riches.

I was reminded of my morning walk a few days later while reflecting on the feast of Pentecost by reading poetry of Jessica Powers (1905-1998) an American Carmelite nun. In “Ruah-Elohim,” she writes that “Spirit” in Hebrew is feminine and that the Holy Spirt is tender Love, come to mother us. In “To Live with the Spirit'” she reminds us that the one who walks as the Spirit-wind blows “turns like a wandering weather-vane toward love.”

But it was her description of the Apostles in “The First Pentecost” that caught my breath. They looked at one another. “…words curled in fire through the returning gloom. / Something had changed and colored all the room. / The beauty of the Galilean mother/ took the breath from them for a little space. / Even a cup, a chair or a brown dress/ could draw their tears with the great loveliness/ that wrote tremendous secrets every place….”

I ache to see with such Spirit-opened eyes, our world and one another. Could wars and hatred, violence and earth-abuse continue among human beings with eyes so wide and seeing? Would eyes of the heart see past the false constructs of “them” and “us” to the “we” that shared Spirit makes us? Ah, for such eyes!

Along with this tired planet, with the weary, war-torn beings that live on it, I join my voice to the urgent prayer:

Come, Spirit come! We need the sight you bring.

© 2021 Mary van Balen

The poem is “Roses.” Oliver writes of the quest to answer life’s “big questions” and decides to ask the wild roses if they know the answers and might share them with her. They don’t seem to have time for that. As they say, “…we are just now entirely busy being roses.”

The poem is “Roses.” Oliver writes of the quest to answer life’s “big questions” and decides to ask the wild roses if they know the answers and might share them with her. They don’t seem to have time for that. As they say, “…we are just now entirely busy being roses.”