First published in The Catholic Times, October 11, 2015 issue

I stayed home from work the morning that Pope Francis spoke to the United States Congress. I wanted to watch his face and the faces of those gathered to hear him: A congress mired in partisan politics, hopelessly polarized. What would Pope Francis say to them? To the country? How would our elected officials receive his words? It was a moment I wanted to witness as it unfolded.

The pope did not disappoint. Just a couple of weeks ago, at a gathering of citizens concerned about issues of social justice and a stalled political system, a gentleman expressed dismay that the concept of the common good was no longer a topic in public discourse. Pope Francis took care of that.

He had barely spoken a hundred words when he directed attention to our solemn responsibility for the common good. “You are called to defend and preserve the dignity of your fellow citizens,” he said to the lawmakers, “in the tireless and demanding pursuit of the common good, for this is the chief aim of all politics.”

By now, most who read this column will have read (or heard) various commentaries on the address and what the pope did and did not say. But, what surprised me was how he said it: He used the example of four great Americans who gave their lives to service and to the betterment of society. Two, Abraham Lincoln and Martin Luther King, Jr., often serve as inspirational examples, fittingly so.

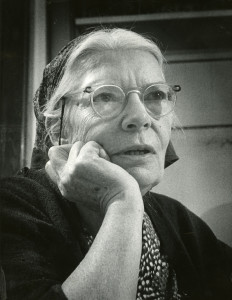

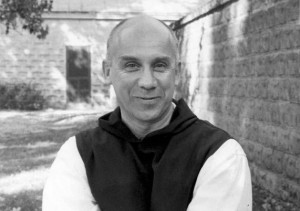

The other two are the ones I didn’t expect: Dorothy Day and Thomas Merton. In my late teens I read a number of their books. They influenced my faith and spirituality. Still, I wondered, how many of the government officials sitting in the room knew those names? How many watching and listening around the country wondered who they were and searched for them on mobile phones and tablets?

They’d find Dorothy Day, born in 1897, was a radical who advocated for women’s suffrage, a pacifist who opposed all wars, and a tireless worker for social justice who saw the need not only to serve the poor she encountered in daily life, but also to change the system that created such poverty and injustice. She was a writer and journalist who gave voice to marginalized people and causes.

A convert to the Catholic faith that fed and sustained her, Dorothy attended daily Mass, read scripture, and wove prayer throughout her days. As a friend who once heard her speak said, “She was prayer.

Dorothy, along with close friend Peter Maurin, founded “The Catholic Worker” newspaper and the movement of the same name. Catholic Worker Houses continue to welcome the poor and are places where the corporal works of mercy are lived out. As Pope Francis encourages, they are places of encounter.

The pope spoke a second name that I didn’t expect to hear: Thomas Merton, a Trappist Monk at the monastery of Gethsemani, in Kentucky. We celebrated the 100th anniversary of his birth this year. Pope Francis singled him out for his openness to dialog with others of all faiths, seeing them as pilgrims on the same search for ultimate truth. His last journey was to Bangkok where he attended an international conference on monasticism, organized by Buddhist monks. Like Day, he calls us to deep encounter with those unlike ourselves.

Pope Francis also recommended Merton’s openness to God in a contemplative style of prayer. Merton in the midst of a world immersed in “noise” of all types—digital, visual, aural—pouring out of players, electronics, out of the depths of our souls, calls us to quiet presence. For those who fill up every moment with activity and distraction, he says, “Be still. Listen.”

Pope Francis also recommended Merton’s openness to God in a contemplative style of prayer. Merton in the midst of a world immersed in “noise” of all types—digital, visual, aural—pouring out of players, electronics, out of the depths of our souls, calls us to quiet presence. For those who fill up every moment with activity and distraction, he says, “Be still. Listen.”

Like Dorothy Day, Thomas Merton was a writer and a convert. His books addressed spirituality and political topics. He was an outspoken critic of the Viet Nam War and the arms race.

Two people of deep faith and prayer: One active in the world, the other a monk responding to world issues with his pen; both social activists who pointedly challenged the status quo and whose words speak to us today. Immigration, poverty, climate change, racism, and violence require bold responses from all of us, not only governments.

If you’re not familiar with Dorothy Day and Thomas Merton, consider reading some of their work or finding out more about their lives and spiritual journeys. Pope Francis’ choices challenge us all.

© 2015 Mary van Balen