This year, the feast of the Annunciation falls just a few days before Palm Sunday and the beginning of Holy Week. The proximity of the two feasts brings to mind the connection between the Incarnation and the Paschal mystery, and these questions: Why did Jesus come into the world and what is the meaning of his death on the cross? Big Questions. Impossible to answer but not to ponder.

Growing up, I couldn’t believe God, who created everything and who loved us all, needed Jesus to be tortured and crucified to make up for the sin of Adam and Eve and the rest of us. I attended Catholic schools and my share of Lenten services, including the Stations of the Cross. Church rituals and liturgies spoke to me, but the Stations of the Cross left me sad and confused.

God loved us and made the earth and everything on it, my teachers said. The stars. The planets. Whatever else was out there. And God was born to be with us always. That’s what Emanuel meant: God-with-us. That image of God didn’t fit with a vengeful Deity who demanded Jesus suffer and die because people sinned.

As I grew, thought the disconnect remained unresolved, it didn’t claim my time or attention. Let theologians hash it out if they must. I ignored the claims of a vindictive God and trusted my experience of a merciful one. I knew there were consequences for sin and that my own contributed to the corruption of the world and to the suffering of the Christ who dwells in all. I knew it affected the planet I live on and that I needed forgiveness and a deep transformation of heart.

But I never believed that God demanded a horrible death to put things right.

Later I learned there were names for theories like this: substitutionary atonement, for example, and that it was not the only theory. There had been and are other ways of understanding what Scripture has to say about the Incarnation, death, and resurrection of Jesus. Of course, God is God with wisdom beyond human imagining. Being “right” isn’t the goal. Yet, human beings look for meaning.

During my studies for an MA in theology, a professor introduced me to the medieval, Franciscan theologian, John Duns Scotus (c. 1266-1308), who did not agree with interpretations that held the Incarnation was necessary because of human sin or that Jesus’s crucifixion was the sacrifice required to pay a debt. The incarnation wasn’t a rescue plan. It was always the plan. Jesus came to reveal the face of Divine Love and to show how it looked to live that out as a human being. Then he asked us to do the same.

Citing John Duns Scotus and the Franciscan “alternative orthodoxy” that he espoused, Richard Rohr, OFM, connects Christmas and Easter: “… Christmas is already Easter because in becoming a human being, God already shows that it’s good to be human, to be flesh. The problem is already somehow solved. Flesh does not need to be redeemed by any sacrificial atonement theory.”

The incarnation led to crucifixion because of the state of the world, not because of God’s demands. Jesus stretched his arms out on the cross because a sinful world could not deal with his radical Love. He stood with the poor, the marginalized, and the oppressed. His life and teaching were threatening to those in power, both political and religious, who kept these people on the fringes. The requirements of Love to forgive, to serve, to embrace the other, to reverence the Divine within every person and treat them with the respect and care all deserve, to love enemies – it was too much to ask. And so, the broken world executed the one who was Love.

And God wept.

This Holy Week, I will remember the Incarnation and the call to participate in Love. I will ponder how my living contributes to it and how it undermines it. I will ask forgiveness. But more than that, I will pray for courage to open my heart and change my ways, to contribute to Love and not to intolerance, hatred, fear, or violence.

The Incarnation says I am with you. The crucifixion says accepting the invitation to follow Jesus’s example of being Love has consequences. The Resurrection says that in the end, Love is what lasts. Always.

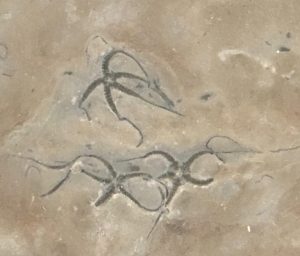

Featured image: Photo taken by author in Saint Johns University Alcuin Library, Collegeville, MN, 2009.

Sculptor: Paul Granlund

©2021 Mary van Balen