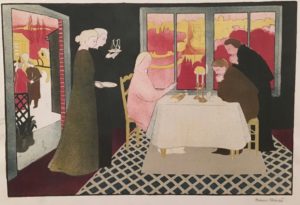

PHOTO: Mary van Balen

There is a Dutch word for doing nothing: Niksen. I know this not because of my Dutch heritage but from an article that made its way to my email inbox.

What does it say about our modern sensibilities that an article about doing nothing and not feeling guilty about it was an internet hit? The value of multi-tasking is being reevaluated and the ability to say “no” to opportunities for going somewhere or doing something is beginning to look as desirable as saying “yes.” Perhaps we’re longing for some “be-ing,” not “do-ing,” time.

The contrast between “be-ing” and “do-ing” is nothing new. From high school days, I heard the phrase “Who you are is not the same as what you do.”

It made sense, but as life unfolded, allowing that truth to filter from head to heart wasn’t easy. In society’s eyes, one’s job reflects one’s worth: A professor is more important than the worker who maintains the school building. A mother who works outside the home is making a greater contribution than the one who chooses to work full time at home.

We value being busy. Our culture espouses achieving, earning what you get, and the idea that hard work brings success.

Not true. Some of the hardest working people aren’t successful in the eyes of our culture. They don’t make big bucks or hold prestigious positions. Sometimes they can’t make enough to meet basic needs. There are lots of realities besides work that factor into “success”: race, privilege, opportunity, socio-economic status, and just plain luck to name a few.

I emailed my cousin in the Netherlands to see what she thought about niksen and if, as the article suggested, it was a part of the Dutch culture. Jeanette responded quickly.

Talking about niksen was unfamiliar to her since it’s something the Dutch don’t think about a lot since it’s just part of their way of life. Unlike many Anglo-Saxon cultures, she said, they are not “ultra work focused.”

“What seems like the difference between our two cultures is that we take time to relax as a rule. We sit down for coffee in the mornings, lunch at lunchtime, and tea in the afternoons. Kids and teachers do the same in school. We incorporate moments free of duty into our days, and they work well for us.”

“Niksen isn’t planned. It is a way to feel free to stop doing things for a minute—or a little longer—and let your thoughts linger on,” she wrote.

It could be putting your feet up and doing nothing or watching rain pour down outside. It’s a bit of time to recuperate for ourselves.

Children can be a good example of that. One of my daughters recounted a morning she recently shared with a friend and two children.

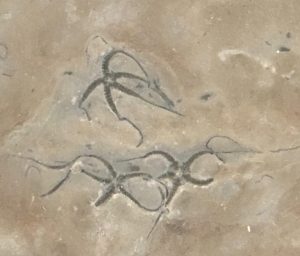

American Dagger Moth caterpillar

Photo: Kathryn Holt

The children hurried through breakfast, looking forward to a promised time in the park. While there, they discovered a bright yellow caterpillar with five bunches of tall, black bristles. The kids were enthralled, and their enthusiasm was contagious. Soon the adults joined in, making little obstacle courses with sticks and leaves, clapping hands when the caterpillar went under rather than over, and apologizing when it fell from an offered stick.

Telling the story, my daughter’s eyes sparkled. “I was as excited as they were,” she said. “So much joy and fun just watching a caterpillar.” Sigh. “It was a wonderful little ‘vacation’ from my adult life.” Niksen.

I imagine that Jesus was good at niksen. Time alone in a boat on the lake or wandering in the wilderness wasn’t always filled with fasting, intense prayer, or planning his next move. I bet he spent plenty of time simply enjoying sunlight sparkling on water or watching clouds changing shape in the sky. From his stories we know he took time to gaze at flowers and observe nature. He liked kids and spent time with friends. The talk wasn’t always serious or the activity always purposeful. He let his thoughts wander and sipped tea or drank wine with friends. Simply resting in Grace. He was a “be-er” as well as a “do-er.”

It’s good to remember. Ecclesiastes says there is a time for everything under heaven. That includes niksen.

© 2019 Mary van Balen

He and his wife were busy folding loads of laundry and sorting it into piles for each of their four children. They were preparing for a month-long trip to visit both sets of grandparents and, in addition to that, camping for a week. In the midst of their preparations, they offered hospitality to a visiting aunt, which would be me. And of course, all four children were around, talking to their visitor and taking care of their own preparations—which may have included cleaning rooms and gathering books to take. I leave it to your imagination. Not a lot of time there to sniff the laundry.

He and his wife were busy folding loads of laundry and sorting it into piles for each of their four children. They were preparing for a month-long trip to visit both sets of grandparents and, in addition to that, camping for a week. In the midst of their preparations, they offered hospitality to a visiting aunt, which would be me. And of course, all four children were around, talking to their visitor and taking care of their own preparations—which may have included cleaning rooms and gathering books to take. I leave it to your imagination. Not a lot of time there to sniff the laundry.

I’m not sure when I began reading books by Thomas Merton. Probably late high school or early college. I’m also not sure how I discovered them. Though I was naturally drawn to contemplative prayer, the word was unfamiliar to me until Merton’s writings provided it. “Contemplative” was not something you heard about sitting in the pews on Sundays or even in religion classes. Not usually. Reflecting on that later, I never understood why. Christianity has a long, rich contemplative tradition.

I’m not sure when I began reading books by Thomas Merton. Probably late high school or early college. I’m also not sure how I discovered them. Though I was naturally drawn to contemplative prayer, the word was unfamiliar to me until Merton’s writings provided it. “Contemplative” was not something you heard about sitting in the pews on Sundays or even in religion classes. Not usually. Reflecting on that later, I never understood why. Christianity has a long, rich contemplative tradition.